If the digital world disappeared tomorrow, we may wonder what would remain. Or what we would rescue from our (figurative) digital house on fire.1 It could all crash and burn, as I learned in the past six months, when I lost my laptop (in a bag, on a train - returned six weeks later) and lost my smartphone (for good - wince).

It hurt. The treasured item for me was my music collection - hundreds of carefully curated playlists, and tens of thousands of mp3s amassed in the 00s and early 2010s. I felt grief - yes, the word fits - for the cumulative effort down the drain, and how I’d directed my attention, for nought.

So I got thinking about how the digital tools we use shape the way we live, love, and make memories.

Since the telegram replaced the posted letter, there has been a steady loss of paper “ephemera” - typically defined as printed or written material meant to be discarded - from communications, for historians and ourselves to look back at. Since the dawn of personal computing, on to the internet, texts, and smartphones, the volume of communications material has grown exponentially, and the tangible physical traces of this lessen.

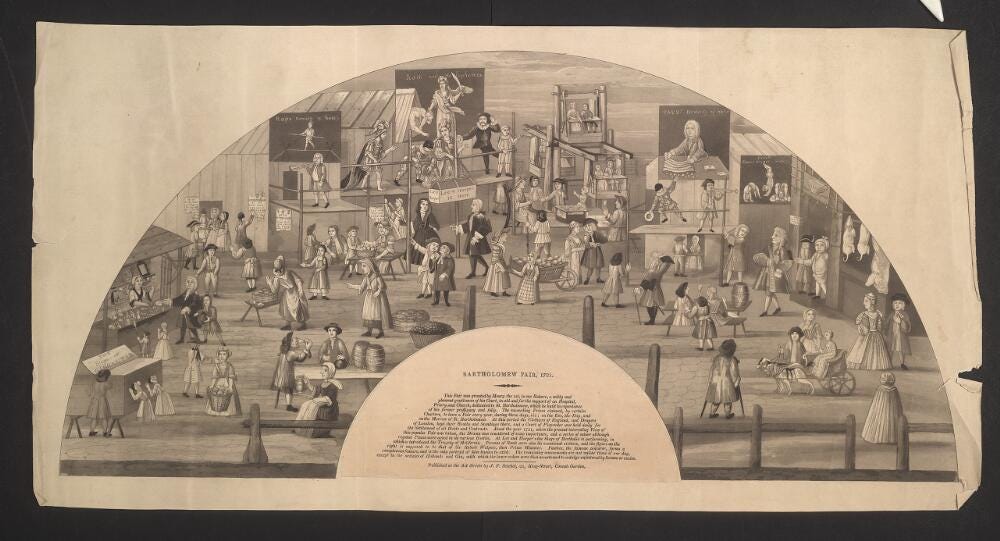

I recently visited an ephemera fair in Bloomsbury, full of tables of well-organised postcards and prints. Amid the hubbub of focused collectors and gentle banter between traders, a joie-de-vivre of material from the past two centuries felt honoured and treasured.

Together in electric dreams

“Who will show your grandkids your love letters on WhatsApp?” someone quipped (I was unable to locate the source). It’s true, this digital life lacks physical, tangible longevity. To print out the early courtship of love would in some ways seems absurdly sentimental. Or in the case of a dating app like Hinge, slightly tainted by the marketplace. A jarring reminder that we were talking to three other people when we complimented, teased and persuaded our love - possibly now married with children - to go on that first, fateful date.

And once you transitioned from the dating app onto text or WhatsApp - and what a moment this is! - the memes you sent each other that made you laugh. That made you discover that this person saw the world in a similar way to you. You closed your emotional distance with a well-chosen Pusheen sticker or sideways-looking corgi. All this will be lost to the digital winds of time.

Perhaps the tokens of treasured memories change. In past centuries, it was common to send a lock of hair as a love token, and the recipient to wear this in a locket. No loss, perhaps. Why pretend we’ve the leisure to unfurl paper and prepare a pen? Physicality can be burdensome, and costly in time. Convenience wins over romance; etiquette evolves for a reason.

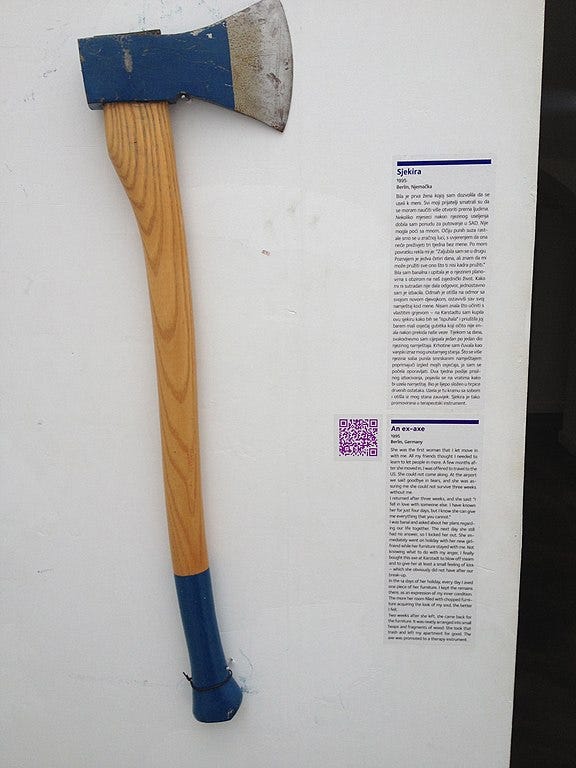

I recently had a breakup. What do I archive, and how? On a phone, I could create a photo album, titled “Exes”, or to nestle it alphabetically nearer the bottom of the list “X - Exes”. This may seem more like a cleanup than cherishing memories, but the purpose is practical. Digitally archiving an ended relationship is borne firstly from the need to clear one’s head. It’s the digital equivalent of taking mementoes of a relationship off the wall, off the fridge, off the shelf. Second, it’s an act of prudence and kindness to any budding future relationship, to avoid their stumbling on photos of an ex.

You closed your emotional distance with a well-chosen Pusheen sticker or sideways-looking corgi. All this will be lost to the digital winds of time.

On social media things are less easy. It’s never been easier to scroll down a new partner’s Instagram a few screens and start to make unhelpful comparisons. You might be snuggling on the sofa, showing photos of your ridiculous pet cat or that time you baked a show stopper… and there’s the former couple, a laser-targeted buzz-kill. When we’re all entrepreneurs of the self,2 our ever-present memories have the power to inflict emotional collateral damage.

Life will go on, in silicon

We can feel uneasy at the idea that our digital ephemera may outlive us. Even the parts worth forgetting: every misjudged emoji reaction, every days-long delay in replying. The red roses of love now fossilised as potpourri, jarringly vivid pixels, as bits and bytes. The chats can be archived, but we increasingly cannot choose what is forgotten. And fortunately, WhatsApps remain private, at least from Government agencies, whilst encryption lasts. Unless in infamy - as disgraced sexting celebrities show us. So much for illicit whispers. It’s private until it’s in court.

The digital ephemera of the dead is a stranger thing. Some years ago, a charismatic, bright-witted university student I debated against, died unexpectedly. When I remembered to look them up a couple of years later, their Facebook profile was full of tributes. The profile photo took on the air of a photo by a gravestone. Below this, scrolling down, news articles they’d shared. A tragic juxtaposition between stream of consciousness and vigil.

Notes to self: aides memoire

It’s never been easier to capture every fleeting thought, observation and idea and thus convert this to data. How we interact with this data can shape our sense of self. There is a new relationship between thought and record. Centuries ago, when paper became commonplace, in Renaissance Florence, notes to oneself exploded in volume. The notebook was born. Today, digital notes are similarly multiplying exponentially.

Everyone has their own method, be it Notes, OneNote, Evernote, Notion, Obsidian, or simply emails to self. I use a combination. For sheer convenience, with a small hack I’ve turned to WhatsApp for notes. Amusingly, if not embarrassingly, now most of my WhatsApps are to myself. Create a group, remove the other person, and voila - a digital room of one’s own.

I cringe to think how many lists I’ve created on various social media platforms: Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram. As the ‘enshittification’ of these platforms with advertising-based visual pollution increased, I made a strategic retreat to solo media. The problem with taking pictures as notes - a kind of photo mania, a visual foraging - is that recording is not the same as processing.

It seems likely that most of us rarely ever look at our digital photo albums. The act of curating our social media streams represents our feeble last vestige of control in the attention economy. We tidy away our life like complete rows in Tetris and - poof - they disappear. (It’s always in the cloud, so why remember?) But there is no ‘cloud’, only server rooms, whirring away.

most of my WhatsApps are to myself. Create a group, remove the other person, and voila - a digital room of one’s own.

Digital humanism

Record-keeping matters for how we conceive both our minds and our lives. Frictionless recordability precipitates the flattening of meaning and ultimately the absence of meaning. True meaning-making is what happens in narrative, or as the fashion has become, in ‘storytelling’. Fragments can become a story of a kind - as modernist and surrealist authors showed - but on the whole, disconnected fragments lack the psychological depth that creates meaning.

Frictionless recordability precipitates the flattening of meaning and ultimately the absence of meaning.

It's up to us to decide what to make tangible and to make meaning from. Otherwise, we're wading through a river of content and everything flows past us. There is a stark contrast between our organic, messy, rainforest selves where memories grow, and the fragile crystal palace offered by digital capture. This is not a call to be analogue, nor a hand-wringing, folksy neo-Luddism. It’s a call to reconsider our digital lives, what is worth recording, and why.

Afterword

I got a new phone. Having had my old one for six years, it wasn’t worth an insurance claim. And my memories? Most of my photos were there, thanks to being fairly diligent with Google photos backups. But the WhatsApps took weeks to load. Some still haven’t. I’m not going to evangelise for the dumb-phone and offline living. But I’m definitely a little slower on the draw. Respecting my brain more.

I reflect that if an experience is important, I’ll remember it. In the big-picture, taking more granular records of my life won’t help me with overwhelm; sometimes it’ll do the opposite. Personal meaning is slow-growth, it resists acceleration. And that’s just fine.

Top image: "On the second anniversary of the fall of the Bastille, Priestley's house was looted and burned down by a mob (inspired by the King and the Church) that was enraged by Priestley's view of revolution." (Norton)

The "Entrepreneur of the Self" is the subjectivity model associated with neoliberalism.

Foucault deals with this subject in his course entitled Birth of Biopolitics (1979), where he presents the genealogy of liberalism and neoliberalism.

It is the subject that acts upon itself to conform to the market. The neoliberal subject is in constant adaptation and competition, proper to the power relations of neoliberal society. (Quora)

Share this post